The men who are standing tall against early marriages in the Gaza Strip

Date:

When two men arrived at Freeh Abu T’ema’s family home in Abasan Alkabeerah, a village located in the south of the Gaza Strip, he didn’t know that his life, as well as his daughter’s, would change forever.

“My 16-year-old daughter’s wedding was approaching,” Abu T’ema recalled. The soon-to-be bride was his third daughter, out of five, all between the ages of eight and 24. She was preparing to drop out of school because her then-future husband did not want her to pursue her education.

“I knew she was too young to get married and didn’t finish school yet, but I couldn’t decline a marriage proposal from one of my cousin’s sons, so I said yes,” said Abu T’ema.

The visitors were Mossa Abu Taema and Wael Abu Ismael, who came to Abu T’ema’s home to stop his daughter’s marriage. Abasan Alkabeerah is one of the most conservative villages in eastern Khan Younis, a border town in the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Early and child marriages are common here. According to the 2017 census by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 21 per cent of registered marriages of 2017 in the Gaza Strip Involved girls under 18 years of age. Nonetheless, both men, also from Khan Younis, believed that marriages cannot be consensual until both parties are at least 18 years old. They had undergone a training delivered by a community-based organization, the Future Brilliant Society, in Khan Younis, as part of UN Women’s Regional Men and Women for Gender Equality Programme funded by the Government of Sweden. The programme focuses on engaging men and boys as change makers to promote gender equality. The training prepared them to become “ambassadors of change” and challenge the tradition of early marriage.

The two advocates presented Abu T’ema with facts about the impacts of early marriage, including potential negative consequences on his daughter’s physical and mental health, as well as the statistically proven higher rate of divorce for early marriages compared to the marriages of couples over 18 years. Abu T’ema listened closely, and, by the end of the conversation, he was convinced. He called off the wedding and his daughter returned to school the next day.

For Mossa Abu Taema, a doctor by profession, child marriage cannot be consensual. “As a medical doctor, I couldn’t bear the negative effects that early marriage brings to a young girl’s health,” he said. “And also, the ethical aspect of it—how can you ask a 13-year-old girl to get married?”

Wael Abu Ismael had spent most of his adult life in Libya, where women usually got married in their mid-20s after finishing university. When he returned to his hometown of Khan Younis, he was shocked to see under-age girls being forced to marry early.

“Many fathers in Khan Younis do not have jobs, so they tend to marry their daughters at an early age to reduce the number of mouths to feed,” explained Abu Ismael. “However, rather than reducing the burden, early marriages typically double it. If there are issues in the marriage, the girl’s parents are often asked to take responsibility.”

Although the men who were selected to become ambassadors of change already had progressive values, “the six-day intensive training on public speaking, [negotiation] skills, and different methods to influence others, helped them transform their beliefs and spark actions to stop early marriage.. [The community members] started to pay attention and their behaviour also began to change,” said Mr. Haitham Abu Teir, the CBO’s coordinator.

The ambassadors have prevented early marriages in 50 families and counting. “Now we have beneficiaries who changed their minds and have become ambassadors themselves, just like Abu T’ema,” said Abu Teir. The initial group of 20 advocates has expanded to more than 30 men in eastern Khan Younis who are determined to end early marriages.

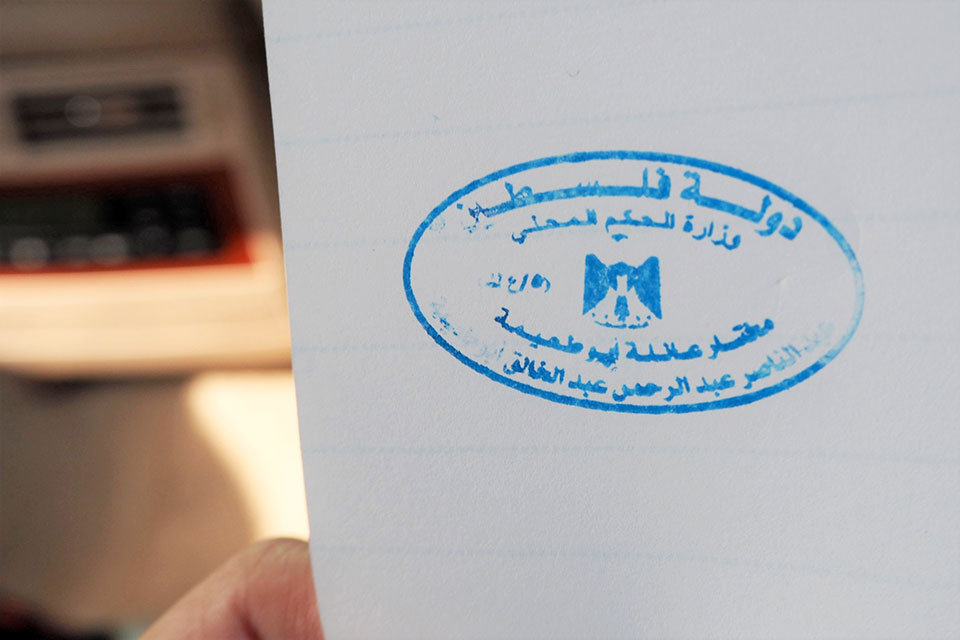

As the movement started growing, the advocates knew they would need the support of community leaders to sustain the momentum and create lasting changes. They engaged the most respected elected figure in the Khan Younis community, the “Muktar”, Abdel Naser Abu Te’ema. The Muktar has decision-making power for community-related matters such as approving marriage contracts.

Previously, Abu Te’ema approved early marriages if it was desired by the family because he considered marriage to be a private family matter. However, after two home visits facilitated by the ambassadors of change, Abu Te’ema understood the negative health effects of early marriage and how the high rate of divorce strains the community.

“The home visits were powerful,” shared Abu Te’ema. “They made me to realize that this tradition should not continue for the future of our community. Since that day, I have not approved of any marriage under 18 years.”

Abu Te’ema has further convinced 10 other “Muktars” in eastern Khan Younis—covering a total population of 30,000—to reject any marriage contracts until both parties are at least 18 years old.

“Working with men from the targeted communities to become change-makers themselves has been immensely successful, especially because it engaged respected and influential men to talk to other men in their own communities about the devastating consequences of child marriage, supported by facts and evidence,” said Hadeel Abdo, Project Coordinator of the Men and Women for Gender Equality programme at UN Women. “The topic of child marriage was selected as it deprives girls of their fundamental rights to health and opportunity to achieve their full potential, reinforcing the existing poverty and injustice, as well as vicious cycle of violence.” While there have been substantial gains, the battle is far from over. “We still face many challenges, and some accuse us of bringing “western ideas” to the community,” says Abu Taema. “Once a father of a 16-year-old girl who’s already three times divorced and with two children, slammed the door on us, refusing to listen.”

“However, with the success we’ve had so far and with the new ambassadors who have joined us to make our community a better place for all, we won’t stop until there’s zero early marriage cases in eastern Khan Younis and the entire Gaza Strip. We believe this is possible.”