Photo essay: Rural women, human rights

Date: 22 February 2018

She is a rural woman who works from daybreak until sundown and often beyond. She may run a small business or cultivate a field or both to support her family. Long hours are spent collecting water and fuel, and preparing food. She sees to the raising of children. She tends livestock.

Without rural women and girls, rural communities would not function. Yet women and girls are among the people most likely to be poor, to lack access to assets, education, health care and other essential services, and to be hit hardest by climate change. On almost every measure of development, rural women, because of gender inequalities and discrimination, fare worse than rural men.

The world has committed to upholding the rights of all women and girls. Fulfilling this commitment is particularly urgent in rural areas. Rural women and their organizations are on the move to claim their rights and improve their livelihoods and well-being. They are setting up successful businesses and acquiring new skills, pursuing their legal entitlements and running for office, using innovative agricultural methods and taking advantage of new technologies.

The following exhibit, sponsored by UN Women, highlights some of their issues and shares some of their stories.

“Women’s rights are human rights. But in these troubled times, as our world becomes more unpredictable and chaotic, the rights of women and girls are being reduced, restricted and reversed. Empowering women and girls is the only way to protect their rights and make sure they can realize their full potential.”

—United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres

Around the world, the United Nations system stands behind the realization of the rights of rural women, in principle and practice. Upholding these rights is essential to international commitments such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, and the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. Fulfilling the promise of the landmark 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, where the goals include gender equality as well as ending poverty and hunger, achieving decent work for all and combatting climate change, largely depends on empowering rural women and girls.

UN development entities, led by UN Women, back progress towards these objectives through assisting implementation of national and local programmes. These directly engage women and girls in rural areas, supporting their efforts to access all the elements fundamental to their rights and well-being, whether health services or land, financing or climate-smart technologies, among others.

Each year, the UN system champions the rights of rural women on the International Day for Rural Women. The Commission on the Status of Women, the principal global intergovernmental body exclusively dedicated to gender equality and the empowerment of women, has called for tearing down the barriers to rural women and girls. In 2018, it tackled the challenges and opportunities they face as a priority theme.

The right to a decent standard of living

Around the world, almost a third of women’s work is in agriculture. Much is time and labour intensive, and poorly paid, without the full protection of labour rights.

Empowering rural women in agriculture can unlock change on many fronts. In Guinea, one of the least developed countries, rural women have gained opportunities to generate income through cooperatives that grow Moringa. The vitamin-rich leaves and pods of the tree are in demand by international markets, and important to preserving biodiversity and preventing erosion. Supported by UN Women, cooperative members share ideas and learn new skills, and have emerged as leaders in improving life in their communities.

Markets are vibrant hubs of economic activity in many places, providing shoppers with a ready supply of fresh fruits, vegetables, fish, grains and other staples. In the Pacific region, up to 90 per cent of vendors are women. They make a living, but hours are long, profits are often low, and conditions difficult. Many come from rural areas and must sleep at the market for days at a stretch, putting them at high risk of gender-based violence and theft.

Women vendors have a right to the full range of protection and support measures that can help make their livelihood a decent one. UN Women’s Markets for Change Programme, supported by the Government of Australia, helps them form associations that give them a more powerful voice in managing markets. Betty Kwanairara has become a market manager. Together, she and other women have successfully lobbied for measures to make markets safe and clean.

Gender discrimination can intersect with other disadvantages in rural communities, which are often limited in access to services, markets, communications and technology. The combination of these factors makes rural women among those most likely to be left behind.

In northern Jordan, an influx of refugees has led to further pressures on limited community resources. UN Women’s Spring Forward for Women programme, funded by the European Commission, has worked with women living in poverty to pursue new sources of income. Munira Hussein created a business selling products made from goat milk. She provides for her family, including a son with disabilities, and has become an inspiration to her community. "Women come to me and ask me about how I started my business. They say they'd like to do the same. I encourage them to do that. Starting a business gives women independence."

“Women come to me and ask me about how I started my business. They say they'd like to do the same. I encourage them to do that. Starting a business gives women independence.”

—Munira Hussein, Jordan, portrayed in the photograph

For many rural women, limited economic opportunities push them to migrate in search of better work and lives. Although migrant women have a diverse array of skills and experience, continuing demand for domestic and care work in many destination countries means these women often fill such jobs. Many find they are not covered by labour laws or basic social protection measures.

Some women migrants land better-paying jobs, including in more advanced forms of agricultural production. Ho Thi Thuy, 29, left Viet Nam to find a higher paying job at a specialized hydroponic lettuce farm in Malaysia. To make the most of the opportunity, she works whatever overtime she can get at a salary considered quite high for agricultural workers.

Technology has increasingly become a tool for women farmers to improve their livelihoods. Even a simple mobile phone can provide ready access to essential information, such as weather forecasts and market prices, which can help women boost productivity and income.

The “Buy from Women” platform in Rwanda was launched in 2016 by UN Women and the World Food Programme, including through a contributions from the Governments of China and Finland. Over 3,000 men and women farmers from 12 maize farming cooperatives tap into a mobile platform that lets them accurately map their plots of land and generate a yield forecast – something that was previously very difficult to do. Among other benefits, they can sign contracts with maize buyers, forging stronger links to markets. The platform also sends regular text messages on new business opportunities, agricultural practices and women’s rights.

The right to land and productive resources

Rural women often have unequal access to land and other productive assets needed for income, food and well-being. This can open the door to additional forms of discrimination and even violence.

In Pakistan, Khateeja Mallah was once a landless farmer. A widow with eight children, she had no legal claim to the land she worked or the crops she grew, and often endured harsh treatment from landowners. Today, through assistance from UN Women, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the International Labour Organization, she finally holds a Land Tenancy Agreement. It upholds her right to farm land, as she proudly puts it, “as far as the eye can see”.

“Now, for the first time in my life I can say something is mine. This land, as far as the eye can see is mine—this paper says so.”

—Khateeja Mallah, Pakistan, portrayed in the photograph

Clean, reliable energy improves health and livelihoods, and eases work burdens inside and outside the home. Yet over 1 billion mostly rural people still do not have access to electricity. Towards a new “energy democracy,” renewable, clean energy should be available and affordable to all, and women, including in rural areas, should participate equally in its distribution and control.

Small-scale, low-cost alternatives, particularly in remote areas and poorer communities, can play a vital role in extending power and making energy democracy a reality. With assistance from UN Women, Musu Junius and Marie Weeks attended Barefoot College solar engineer training in India and have used new skills to electrify their community in Liberia. Behind them, a teacher prepares for evening adult literacy classes made possible by switching on the lights.

Laws and legal practices must uphold women’s equal rights to land, and women should be equally represented in all collective decisions on using land and natural resources. Rural women also must be able to acquire skills, finance and technology to make the best use of productive assets.

Mirjana Hemon moved to a rural area in Serbia in the hope that her husband’s failing health would improve. Soon after, he passed away. In possession of orchards and land, she set up a local association of widows and started a business in rural agro-tourism as well as one to produce preserves and traditional drinks using her own fruits and vegetables. Training and a grant from a programme to support gender equality helped her start her business and make it a success.

Women organizing together can claim a full spectrum of economic, political, social and environmental rights, including through steering public policy decisions.

In Quito, rural women activists from Bolivia and Ecuador gathered to articulate their demands, such as better access to land, credit, training and technology. “It is time to recognize rural and Indigenous women that work the land and produce food for the people. Without us the land would be lifeless, that is why public policies should consider us not only because we are women or Indigenous, but because we are pillars of life,” said Felipa Huanca Llupanqui (far left), Executive Secretary of the Indigenous National Confederation of Native Peasant Women from Bolivia.

“It is time to recognize rural and Indigenous women that work the land and produce food for the people.”

—Felipa Huanca Llupanqui, Executive Secretary of the Indigenous National Confederation of Native Peasant Women from Bolivia, portrayed in the photograph

The right to live free from violence and harm

Rural women are at greater risk of experiencing multiple forms of violence and harmful practices. Violence can occur in homes, places of work, or in public spaces, such as while women and girls collect water or firewood.

In six Indian states, a special education programme supported by UN Women and a local non-governmental organization helps women understand their right to live free from violence and to protect themselves from the scourge of human trafficking.

Higher levels of poverty, limited access to justice and entrenched discrimination are among many factors that put women and girls in rural areas at increased risk of violence. Rural girls are more likely to become child brides than their urban counterparts worldwide.

In Ethiopia, Mulu Melka, 13, raises her hand to answer a question in school. She has twice evaded forced marriage and is determined to finish her education. "Girls need to be educated so they can be self-reliant and know how to protect themselves," says Mulu, who plans to be a teacher.

“Girls need to be educated so they can be self-reliant and know how to protect themselves.”

—Mulu Melka, student, Ethiopia, portrayed in the photograph The right to food security and nutrition

The human right to food underpins all other human rights, and is one in which rural women play a major role as they grow and prepare much of the food consumed by their families. Yet food security and nutrition are increasingly undermined by industrial agriculture, conflict and climate-related shocks.

In a remote village in Bangladesh, a young woman sorts rice. Her harvest must last a long time, as the weather usually allows cultivation only once a year.

Gender discrimination limits rural women’s rights to food security and nutrition in multiple ways, constraining access to agricultural technology and credit, and to knowledge and essential services.

In seven countries, UN Women, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the International Fund for Agricultural Development and the World Food Programme are collaborating on a joint programme funded by the Governments of Norway and Sweden. The programme supports women in breaking through discriminatory barriers. They gain adequate food and income, and become empowered farmers, entrepreneurs and agents of change.

One participant is Maria Quej San de Moran, who smiles watching her garden grow in her village in Guatemala.

“With what we cultivate, we support our household income. My husband cultivates corn, beans and yucca for the market. At home, where the whole family participates, we cultivate tomato, cabbage, pepper and indigenous herbs; now we eat better.”

—Maria Quej San de Moran, farmer, Guatemala, portrayed in the photograph

Drought, increasingly severe and common in a changing climate, means much more than water scarcity. For many of the poorest rural women and girls, it requires spending hours a day fetching water instead of on more productive activities. It can lead to higher rates of violence and poverty, hunger and an increased likelihood of dying during childbirth.

Turkana county is one of the most arid areas of Kenya. Several years of inadequate rainfall have pushed coping capacities to the brink. Women not only struggle to collect enough water, but when food is scarce, they eat less than men. UN Women works with Kenya’s National Drought Management Authority to ensure that all interventions take the rights and needs of women and children into account.

“We don’t have anything for lunch and even in the evening, it depends. If we get it, fine, if we don’t, we will still sleep. Whenever we wake up, we do not anticipate any meal. On a good day, we have a single meal.”

—Adikor Lopunga Nangiro, farmer, Kenya, portrayed in the photograph

The right to a healthy, educated life

Health care for many rural women is out of reach or poor in quality. Privatization can impose additional costs, felt most acutely by the poorest women. Poor health and lack of reproductive rights can compound other deprivations, limiting rural women’s and girls’ well-being and perpetuating gender inequality.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a partnership between five United Nations agencies and the World Bank, known as H6 and funded by the Governments of Canada and Sweden, is improving the chances that rural women will have safe pregnancies and deliveries. Training has improved the skills of midwives. New facilities accommodate women at risk of complication in the last stages of pregnancies so they do not have to travel long distances once labour starts.

Education is a cornerstone of individual and social well-being, shaping informed and productive citizens. It should teach the next generation, girls and boys alike, how to read, write and calculate—and how to strive for a more equal world, free of gender discrimination. Schooling should not be sidelined by early marriage or pregnancy, or inaccessible due to barriers such as language or location.

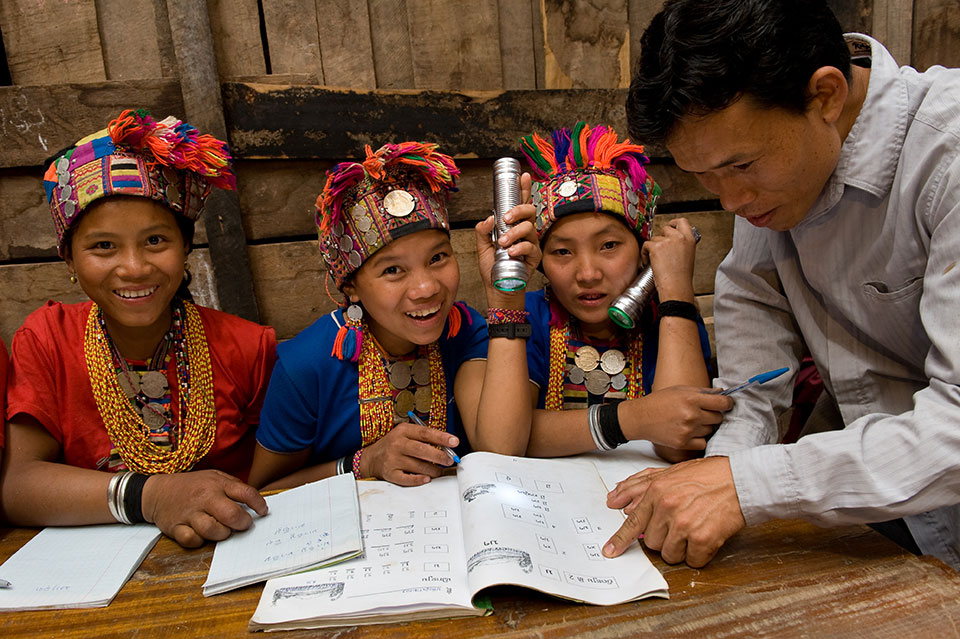

In a remote village in Lao People’s Democratic Republic, young women study the national language.

A number of developing countries are now ageing at a rapid rate, and will be old long before they are rich. Among those most vulnerable to poverty in old age are rural women, who are less likely to have sufficient savings and assets to support themselves. Many live in places where traditional social safety nets provided by families are eroding, including through the migration of younger people to cities.

Rural women have the right to well-being at each stage of life, a principle supported by social protection programmes that ensure basic income and essential health care. Lifelong learning helps an older woman in Georgia retool skills that open continued opportunities for income.